Micro-frontends are the present and the future for scaling large client-side applications. Why should you implement this architectural style? Let’s dig into the reasons that led me and my team to adopt it.

Working at scale is one of the main goals of modern software engineering. Micro-frontends is an architectural style and a technique many organizations are adopting to address this problem. Generally speaking, the motivations for using this approach are basically the same that makes us choose micro-services in the “backend” world: breaking down a monolithic codebase into micro-apps, each of which developed by autonomous team, responsible for the entire lifecycle of this portion of the project.

This approach has the main benefits of improving the development process and the developer experience, because each team is focused on a smaller scope and it can independently deploy new features adapting to changes with a high velocity. In other words, micro-frontends inherit microservices well-known benefits such as development agility, technological freedom, and targeted deployments.

We pay for this high encapsulation of business rules and this high flexibility for each team with an increased effort for infrastructure since automation is one of the key requirements for a successful implementation. Modern cloud technologies greatly simplify this work and can be considered the enabling technologies for this architectural style. Despite this, a distributed system is intrinsically more complex than a monolithic one, because we must take in consideration aspects such as orchestration, distributed failures, observability, and automated deployments.

Objectives & Principles

For the purpose of the article, we can consider our initial architecture as a classic client-server application where the PHP server is responsible for generating HTML pages and JavaScript client side code is responsible for making these pages interactive. We need to evolve the user experience making the user interface more responsive and more app-like. We also need to improve the developer experience because maintaining this legacy codebase has become overwhelming and the team was not so fast to adapt to ever evolving requirements. The final objective of this architecture migration is to improve the user experience, modernize the user interface and speed up the development process, and we would achieve this purpose satisfying the following objectives:

- Independent artifacts: team should be able to independently deploy their frontend applications with minimal impact to other services. Other teams should consider other micro-frontends more or less like a black box.

- Easier maintenance: each micro-frontend module should be developed in isolation and the developer has lower cognitive load when developing a feature or debugging. Each micro-frontend has a separate and decoupled codebase from the others and each of them represents a business subdomain. For this reason it’s easier for a developer to become a (sub)domain expert.

- Autonomous teams: each team should be responsible for making the right choices for its module.

- Technology independence: the legacy framework and tooling should coexist with modern technologies allowing to evolve the codebase without struggling.

- Scalable development: each micro-frontends should be independent from each other so each team could deploy at its own pace, increasing the development speed.

Challenges

As it often happens in software engineering, every choice comes at a cost or at least with some aspects to take into consideration. Choosing a micro-frontends architecture requires facing these challenges.

- Parent/child integration: The micro-frontend architecture involves loading different modules to compose the UI of an application. This requires defining the communication modalities between the loaded micro-frontends that guarantee the performance, the consistency of the user experience that is expected from a monolithic application and, at the same time, the low coupling between the modules. Many of the implementation strategies involve creating an app shell that acts as an orchestrator of the micro-frontends.

- Operational complexity: A micro-frontend application involves creating and managing separate infrastructure for all teams. Automation is a critical aspect of the implementation to ensure scalability of the system.

- Consistent user experience: Child applications should use the same design system of the parent application. This could be particularly difficult when evolving a legacy application because sharing the same UI components and CSS libraries is not an option.

Implementation

First of all, let’s briefly describe the application domain which is useful to understand our choices.

Nuvola is a web application that offers a range of services that fully cover the needs of schools, from teaching to administration. Teachers use the software for teaching management, insert lesson topics, assignments, grades, absences, etc. Instead, the primary purpose for parents and pupils is to read the data entered by the teachers. Finally, the school secretariat uses it to fulfill administrative burdens, registration of documents, communications, personnel management, etc.

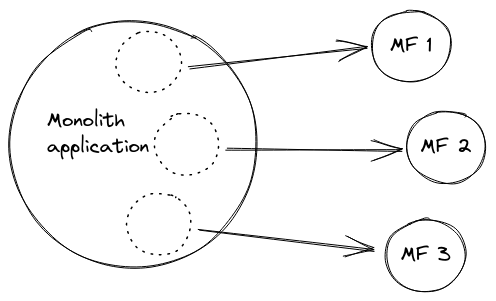

The core concept is to apply a Strangler Pattern in order to gradually eliminate the original application by replacing each sub-domain with a micro-frontend. Adopting the Pattern in combination with a micro-frontends architecture can enable the frontend team to independently deploy each application module and increase the parallelism of development.

We followed the Micro-frontends Decision Framework as a guide for top-level architectural choices. This is a super-short summary of our decisions.

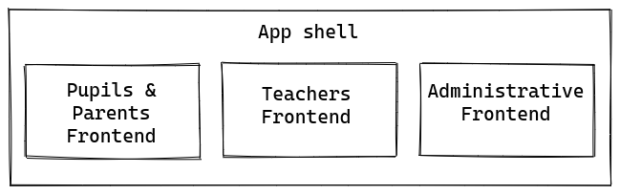

- Definition: vertical split. Every page displays a single micro-frontend and there’s an orchestration layer responsible for switching micro-frontends. We identified a subdomain with a type of user, so each micro-frontend is a micro-app serving a single type of user.

- Composition: client side. A tiny layer of JavaScript code is responsible for loading micro-frontends on the page. In our architecture, switching between micro-frontends is a residual use case because it can happen only for users with different roles, like both teacher and parent in the same school.

- Routing: client side. Since we compose micro-frontends client side, delegating the routing responsibility to the same JavaScript code is the go-to choice.

- Communication: local storage. Previous choices aim to enforce encapsulation and minimize the need for communication between micro-frontends, so the only thing we need to share is authentication. In future developments, if the modules need to share something more, we will likely rely on a loose communication system, such as an event emitter.

The following diagram shows a simplified version of the micro-frontends that will replace the monolith.

We chose to attach parent and child using a run-time integration via javascript because it’s one of the most flexible ways to do that. Each micro-frontend exposes an entry point and a rendering function. The app shell knows the list of entry points of the available micro-frontends and is responsible for loading them on the page.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

<html> <head> <title>Parent application</title> </head> <body> <script> const microFrontendEntries = { '/pupils-area': 'https://pupils.frontend.madisoft.it/pupils.js', '/teachers-area': 'https://teacher.frontend.madisoft.it/teacher.js', '/administrative-area': 'https://administrative.frontend.madisoft.it/administrative.js', }; const microFrontendScript = document.createElement('script'); microFrontendScript.src = microFrontendEntries[window.location.pathname]; document.body.appendChild(microFrontendScript); </script> </body> </html> |

This example is a basic implementation of the app shell. Once the micro-frontend is loaded on the page it renders the corresponding content. In our configuration, the app shell does not render anything: it’s only responsibility is to load and orchestrate micro-frontends.

Full disclosure: at the time of writing, each micro frontend is served by separate HTML pages, and the server is responsible for redirecting the user to the corresponding micro frontend HTML. Future release, will adopt the implementation described previously.

Deployment pipeline

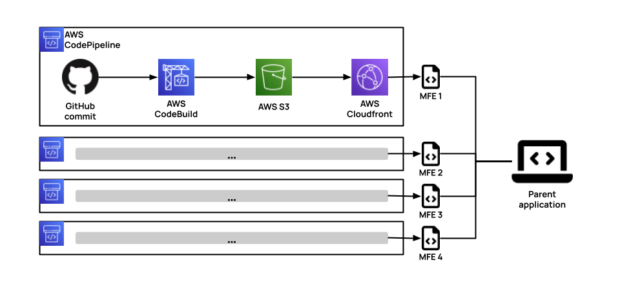

AWS CodePipeline orchestrates the pipeline steps.

- A new commit is pushed to the repository main branch, triggering the deployment.

- AWS CodeBuild clones the latest version of the code from the repository and runs the build commands that install dependencies, transpile and minify code. The build step produces static assets: JS, SVG, CSS, HTML files.

- Build output is transferred to an S3 bucket.

- AWS CloudFront serves static assets to the parent application.

A side note on assets caching

A popular performance optimization technique for serving static assets is to set a long cache expiration time and generate dynamic file names by including the content hash. When connecting micro-frontends together, their entrypoint must be stable and can’t be dynamically generated with the content hash algorithm. So the solution we adopted is to generate a manifest file which maps the micro-frontend name with the dynamic name of the entry point. The manifest file must never be cached or, at most, it can be saved in a shared cache (CDN) that we can invalidate at each deployment.

Cache is configured on our S3 origin setting Cache-Control header appropriately.

- Manifest file:

Cache-Control: max-age=0, s-max-age=2592000// 1 month on shared - All other assets:

Cache-Control: max-age=31536000// 1 year

Webpack Module Federation

On 10/10/2020, Webpack 5 was released. We are already distributing our first version of the micro-frontends solution based on the code previously presented. However This release is shipped with the Module Federation plugin which abstracts the parent child integration in a very effective way. Being a Wepack plugin, we just upgraded Webpack to version 5 and we were ready to use it.

Put it simply, Module Federation allows to assign to each module the role of host or remote.

- Remote modules can be considered independent and expose one or more entry points.

- Host modules are containers that know entry points of remote modules and can therefore use them.

There’s a lot more things going on but this is the core concept. For instance, Module Federation allows each module to be both remote and host at the same time or can handle shared libraries avoiding the user downloading shared libraries multiple times when it is a dependency of many micro-frontends on the page.

Here’s an example of configuration for a remote module.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

const { ModuleFederationPlugin } = require("webpack").container; const deps = require("./package.json").dependencies; module.exports = { plugins: [ new ModuleFederationPlugin({ name: "RemoteApp", filename: "remoteEntry.js", exposes: { "./renderMFE": "./src/index", }, shared: { react: { requiredVersion: deps.react, singleton: true, }, "react-dom": { singleton: true, requiredVersion: deps["react-dom"], }, }, }), ], }; |

This configuration declares a remote entry for a module called RemoteApp that exposes a renderMFE function. Moreover, it declares two shared libraries react, and react-dom.

It could seem counterproductive to share something between micro-frontends, instead, avoiding a multi-framework approach keeps the project more cohesive and more maintainable. However, we know this is a very valuable possibility because we probably need it during further steps of migration to allow the coexistence of jQuery and React, for the small period of time we need to completely migrate our codebase.

What’s next?

At the time of writing this article, we have completed the migration of the parents and pupils area and we have noticed an increase in the use of this section by our users. This for us means that the update has been well received and has fixed at least some of the usability issues that made it less user-friendly. Secondly, we have seen a relative reduction in the cost of our cloud architecture due to adopting the API model compared to generating HTML on our main servers. Infrastructure costs have grown in absolute terms due to two factors. Our user base is constantly growing, more and more schools are choosing to use Nuvola as a management software and as an electronic register. The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic has generated greater use of our software which has represented the official software solution for communicating with schools during the distance learning period.

Given the excellent results obtained, we are already working on the migration of the other parts of the software using the same principles already implemented. Surely Webpack Module Federation will play a key role in this process and will be used for an even simpler and more immediate orchestration.

Thanks for reading so far, I will share more details of our journey in future posts. Keep following us on our blog.

By Mirco Bellagamba, Software engineer, frontend specialist.

Great article, compliments.

I’d like to share a little comment on caching, hoping this could be appreciated 🙂

In my humble opinion the approach of invalidating shared-caches should be avoided as much as you can, because we (wrongly) assume the only shared cache between our site and the end-user is our own CDN .. but there could be a number of other shared caches .. and on them you have no control, so you can’t invalidate them.

My opinion is to set “s-maxage” to a reasonable value that you can take as the “minimum acceptable delay” to have your new deploy really online. For example 10 minutes or half an hour. You are not charged for costs for traffic between CF and an S3 origin.

I’m also not so sure about the real benefit of splitting max-age and s-maxage … as before, you could for sure tolerate a 10 mins lag in the update after a new deploy .. but this point depends on your app needs and max-age=0 is a legit choice for sure (to avoid to reduce CF billing, even a few seconds cache could reduce a lot the traffic).

My 2 cents

Thanks for the comment, I really appreciate this kind of feedback. In a first configuration we did not set s-maxage. In a later phase of the project we introduced it to further optimize performance, and eliminate the time required for downloading from the origin S3 (even if minimal).

We have not encountered any issues with this setup so far but I will investigate further and consider returning to the initial setup (without s-maxage). Thanks again for the tip.